Skull-drilling: The ancient roots of modern neurosurgery

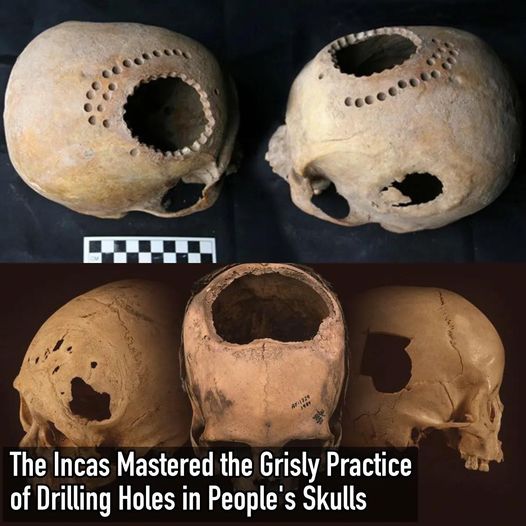

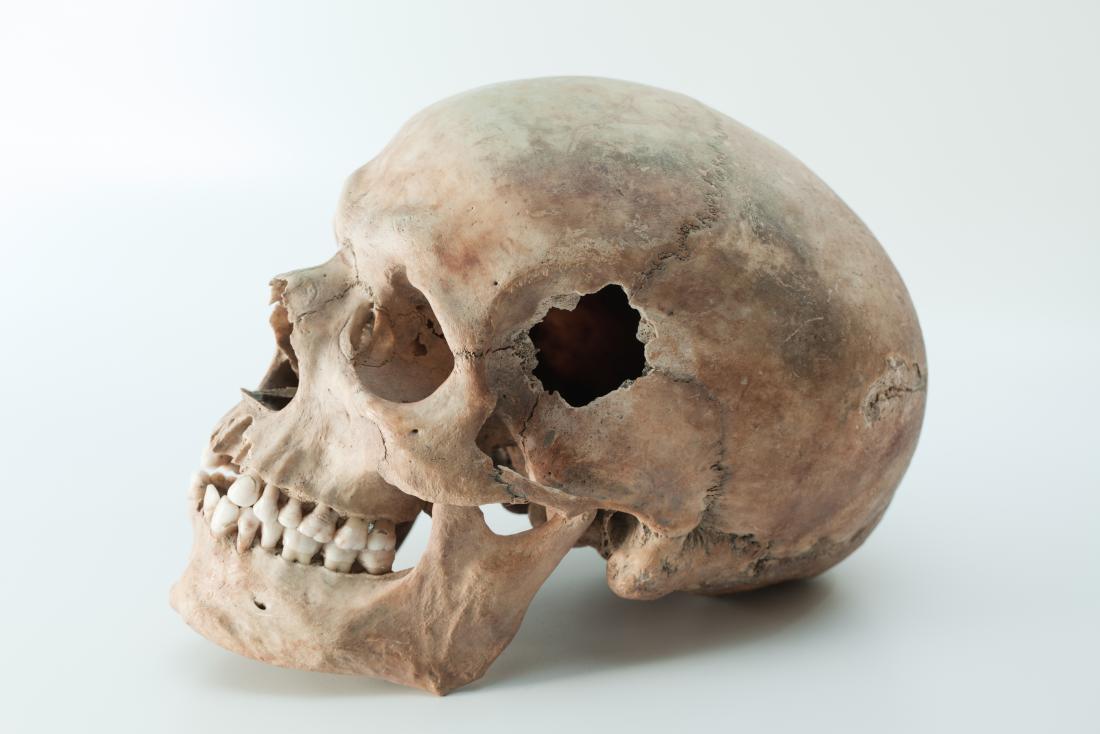

Over the years, archeologists across the world have unearthed many ancient and medieval skeletons with mysterious holes in their skulls. It turned out that these holes were evidence of trepanation, an “ancestor” of modern brain surgery.

Evidence of holes being drilled into the skull for medical purposes, or “trepanation,” has been traced back to the Neolithic period — about 4000 B.C.Trusted Source — and it might have been practiced even earlier.

When it comes to the reasons why trepanation was practiced at all, opinions differ.

The operation may have been performed for various reasons across civilizations and eras.

Some of the trepanations may have been done for ritualistic purposes, but many others were probably performed to heal.

In a medical context, research has shown that trepanation was likely used to treat various types of head injuriesTrusted Source and to relieve intracranial pressureTrusted Source.

Fascinatingly, the most cases of ancient trepanation have been found in Peru, where it was also also seen to have the highest survival rate.

A new study, in fact, shows that trepanation performed in the Incan period (early 15th–early 16th century) had higher survival rates than even modern trepanation procedures, such as those that were performed during the American Civil War (1861–1865) on soldiers who had suffered head trauma.

Dr. David S. Kushner, a clinical professor of physical medicine and rehabilitation at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine in Florida, alongside world expert on Peruvian trepanantion John W. Verano and his former graduate student Anne R. Titelbaum, explain — in an article that is now published in the World Neurosurgery journal — that trepanation was surprisingly well developed in the Inca Empire.

“There are still many unknowns about the procedure and the individuals on whom trepanation was performed, but the outcomes during the Civil War were dismal compared to Incan times,” says Dr. Kushner.

“In Incan times, the mortality rate was between 17 and 25 percent, and during the Civil War, it was between 46 and 56 percent. That’s a big difference. The question is how did the ancient Peruvian surgeons have outcomes that far surpassed those of surgeons during the American Civil War?”

Dr. David S. Kushner

ncient Peruvians vs. modern Americans

The researchers suggest that one reason why skull-drilling practices during the Civil War may have had such dismal outcomes was the subpar hygiene involved in such operations, wherein surgeons used unsterlized tools and their bare — perhaps unclean — hands.

“If there was an opening in the skull [Civil War surgeons] would poke a finger into the wound and feel around, exploring for clots and bone fragments,” Dr. Kushner says of the gruesome practice.

At the same time, he admits, “We do not know how the ancient Peruvians prevented infection, but it seems that they did a good job of it.”

Dr. Kushner also believes that the Peruvians may have used something akin to anesthetic to make the procedure more bearable, and his first guess is coca leaves — which have been used for medicinal purposes by Andean populations for centuries.

“[We still do not] know what they used as [anesthetic], but since there were so many [cranial surgeries] they must have used something — possibly coca leaves,” Dr. Kushner surmises, though he concedes that other substances may also have been employed.

The fact that the ancient Peruvians were clearly doing something well when it came to trepanation is supported by the evidence of over 800 prehistoric skulls bearing between one and seven precision holes.

All of these skulls were discovered along the coasts or in the Andean regions of Peru, with the earliest skulls dated as early as 400 B.C.

Very high survival rates for ancient patients

Combined evidence — detailed by John Verano and colleagues in a book published 2 years ago, Holes in the Head: The Art and Archaeology of Trepanation in Ancient Peru — suggests that the ancient Peruvians had spent many a decade perfecting their trepanation knowledge and skills.

At first, in around 400–200 B.C., the survival rates following a trepanation weren’t all that high, and about half of the patients did not survive, the researchers argue. The team was able to assess the outcomes by looking at how much — if at all — the bone surrounding the trepanation holes had healed after the procedure.

Where no healing seemed to have occurred, the team thought it safe to conclude that the patient had either survived for a short period of time or had died during the procedure.

When, to the contrary, the bone showed extensive remodeling, the researchers took it as a sign that the person operated upon had lived to tell the tale.

Dr. Kushner and team found that, based on these signs, in 1000–1400 A.D., trepanation patients saw very high survival rates, of up to 91 percent in some cases. During the Incan period, this was 75–83 percent, on average.

This, the researchers explain in their paper, is due to ever-improving techniques and knowledge that the Peruvians acquired over time.

One such important advance was understanding that they should be careful not to penetrate the dura mater, or the protective layer found just under the skull, which protects the brain.

“Over time,” says Dr. Kushner, “from the earliest to the latest, they learned which techniques were better, and less likely to perforate the dura.” He continues, “They seemed to understand head anatomy and purposefully avoided the areas where there would be more bleeding.”

Based on the evidence offered by the human remains uncovered in Peru, the researchers saw that other advances in trepanation practice also occurred.

Dr. Kushner goes on to explain, “[The ancient Peruvians] also realized that larger-sized trepanations were less likely to be as successful as smaller ones. Physical evidence definitely shows that these ancient surgeons refined the procedure over time.”

He calls this ancient civilization’s progress when it came to this risky procedure “truly remarkable.”

It is these and similar practices that — directly or indirectly — have shaped modern neurosurgery, which has a high rate of positive outcomes.

“Today, neurosurgical mortality rates are very, very low; there is always a risk but the likelihood of a good outcome is very high. And just like in ancient Peru, we continue to advance our neurosurgical techniques, our skills, our tools, and our knowledge,” says Dr. Kushner.