Sacsayhuaman: Ruins of a Magnificent Inca Fortress

Foreigners often have difficulty pronouncing Sacsayhuaman, so tour guides joke that Sacsayhuaman sounds a lot like “sexy woman” in English.

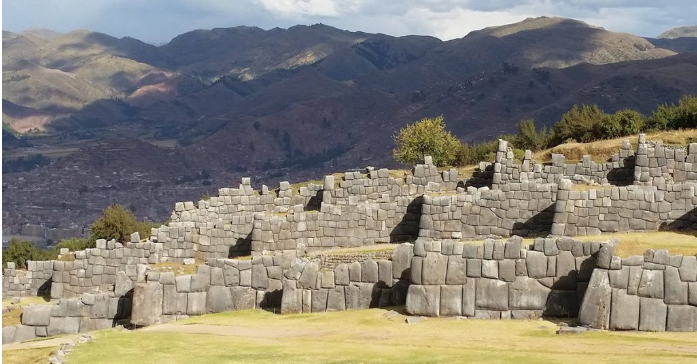

The archeological site of Sacsayhuaman, located on a high hill above Cusco, is characterized by colossal stone pieces weighing several hundred tons. Inca builders cut and polished these huge stones to form into terraces of zigzagged walls that extend hundreds of feet. Although only a small portion of the original site remains, Sacsayhuaman’s Cyclopean dimensions continue to inspire awe at the scale and audacity of Inca stone architecture. Over the course of many centuries, the site has been a mute witness to a millenarian history of pre-Columbian state-formation, European colonization, struggles for independence, and the making of contemporary Peru.

The Fortress: Sacsayhuaman’s role as Cusco’s defender

The initial expansion of the Inca Empire provides the context for the history of Sacsayhuaman. Until the early 15th century, the presence of rival populations, especially the Chanca confederation of the central highlands, limited the ability of the Cusco kingdom to expand territorially. In the year 1438, the Chanca attacked Cusco. Pachacutec, son of Viracocha Inca and second in line to the throne after his brother Urco, led a successful defense against the invaders. For this outstanding achievement, Pachacutec was crowned as the new Inca and he began a series of military campaigns against Cusco’s neighbors, thus marking the formal beginning of the “Imperial” age of the Inca state.

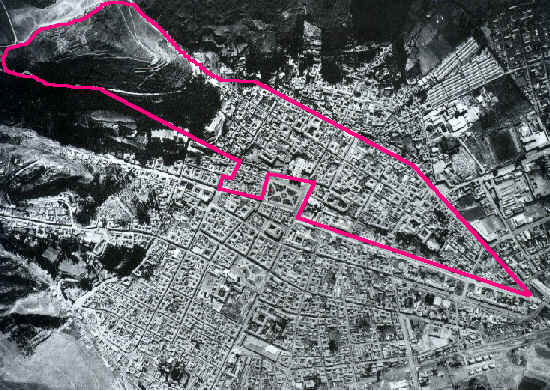

To celebrate his triumphs and as part of his imperial vision, Pachacutec commanded his architects to redesign the entire urban trace of Cusco city to resemble the figure of a puma. Sacsayhuaman represented the head of the feline. Aside from its figurative role, the site also served as a center of political control and logistical support and as a stage for religious ceremonies.

This connect-the-dots image shows Sacsayhuaman strategically placed as the felines head.

Photo by PromPeru

Pachacutec’s rule was a lengthy one (1438-1471), but the building of Sacsayhuamann required nearly a century and was not completed until the eve of the Spanish conquistadors’ arrival to Cusco in 1533. In his post-conquest history of the Inca Empire, the mestizo chronicler Inca Garcilaso de la Vega (1539 – 1616) son of a Spanish colonial official and an elite Inca woman, wrote that the construction project demanded the lives of approximately 20,000 men over the course of several decades. Much of the stone used to build the complex was brought from quarries located 16-32 kilometers (10-20 miles) away across very hilly terrain. Without the use of wheels, vast numbers of laborers were needed for the sole purpose of transporting the huge stones. The fortress is thus representative of the Incas’ capacity to mobilize natural and human resources for imperial goals.

Sacsayhuaman was dismantled in the years following the Spanish Conquest. For generations, its stones served as construction material for Cusco’s churches and houses. It was not until the 1940s that residents began to respect the value and significance of the site and organized to protect it.

In 1944, Cusco residents started to stage reenactments of the pre-Columbian ceremony, Inti Raymi. Performed on the date of the austral solstice (June 24), the ritual pays homage to the Sun, the most important Inca deity. The key performances of Inti Raymi take place on the esplanade of Sacsayhuaman. In the present day, cultural patrimony policies to preserve the site are adamantly enforced.

Views and sights: Get a feel for the history

Only about twenty percent of Sacsayhuaman’s original buildings and structures remain intact. Visitors can nonetheless appreciate a handful of interesting and hidden details in this monumental structure.

Sacsayhuaman’s baluartes are the site’s primary defensive feature, and consist of staggered walls with a saw-like appearance. These walls are built with enormous stones averaging between nine and a couple of hundred tons. By creating multiple layers of combat both vertical and horizontal, the bulwark construction provides a highly tactical position to defend against attacks

The stones at Sacsayhuaman are large and oddly shaped.

Photo by Latin America for Less

Curiously shaped stones can be found throughout the complex. The “paw” is a set of stones that resemble a mountain lion’s paw. The “throne,” also known as K’usilluc Jink’ian, is presumably where the Inca presided over important ceremonies. It is located directly above the main esplanade of Sacsayhuaman, with a view over the entire fortress as well as the neighboring hills and the city of Cusco.

Chronicles written after the conquest tell of three tall towers at Sacsayhuaman. Their positions are indicated by faint outlines on the highest sections of the ruins. The Muyucmarca tower is often mistaken for a solar calendar due to its circular shape, but in fact this was once the political core of the entire complex. This structure had multiple functions, serving as a defensive tower, a reservoir for water and food, an arms depot, and a temple. It complemented the Paucamarca tower, devoted to religious purposes, and the Sallacmarca tower, devoted to logistics.

Looking southeast from the highest terrace where the towers once stood, Ausangate mountain is visible – it is the most important peak in the Cusco area and the site of the gorgeous Ausangate Trek. The Cristo Blanco (White Christ statue), erected in 1945, is walking distance from the archeological site.

Ausangate and Cristo Blanco seen from Sacsayhuaman.

Photo by Matthew Barker

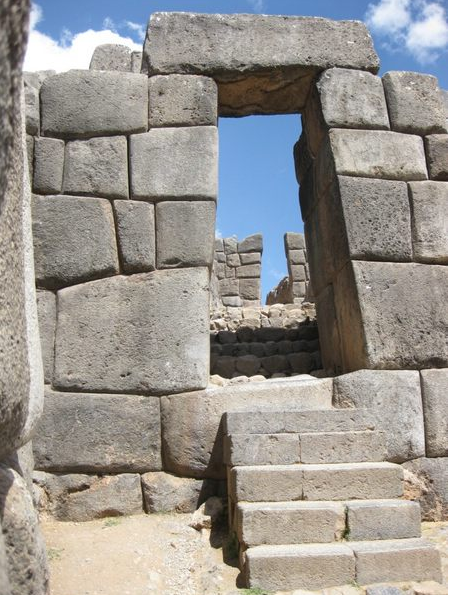

A few surviving gates signal the different areas and layers of the complex. Garcilaso de la Vega gives the sole account of the names of these gates: Tio Punco, Acahuana Puncu, and Huiracocha Puncu. Most of these gates are now gone – like Sacsayhuaman’s other structures, they were dismantled in the period after the conquest. The smaller Puma Puncu (or Gate of the Puma) is one of the few remaining examples of these gates.

The Puma Puncu of Sacsayhuaman.

Photo by Madeleine Ball/Flickr

Many travelers visit Cusco and Sacsayhuaman in June in order to witness the many celebrations, such as Inti Raymi (June 24), that unfold around this time. However, the “fortress” is worth a visit at any time of year as it is, after Machu Picchu and Ollantaytambo, the most imposing example of Inca architecture and urbanism. The defensive baluartes are a wonder of ancient archeology and military architecture. The hydrology of the site and a system of water tunnels known as chincanas continue to amaze specialists with its design. All of this is located just a few minutes from the main square of Cusco.

How to get there

Sacsayhuaman sits at an altitude of 3,700 meters (12,140 feet) above sea level on a hill overlooking Cusco City. It covers an area of about 12 square miles. The location is ideal for the original purpose of the complex, which was to survey and protect the city from external attacks, while its large esplanade also served as a place for rituals and political functions. Today, it is the principal stage for Cusco’s Inti Raymi festival in June.

A satellite view of Sacsayhuaman’s fortress that details its monolithic walls.

Photo by Google Earth

By car: The faster and easier route is to take a car or taxi. From the Plaza de Armas, a standard taxi fare is approximately S./10 (US$2-3), and the ride takes no more than ten minutes.

Walking: If you don’t mind a heart-thumping climb up steep, cobbled lanes, walking to Sacsayhuaman is an option. The most popular route is to take Cordoba Street up to the Nazarenas Square, and then Nazarenas and Pumacurco streets all the way to the ruins. This is a 30-45 minute walk depending on pace. The views of Cusco along the way are exceptional.