Rome in the Footsteps of an XVIIIth Century Traveller

Ancient temples, theatres, triumphal arches, colonnaded streets can be seen at many archaeological sites, but only Pompeii retains such a large number of “ordinary” houses which have not been destroyed/modified, because they were covered by the ashes of the 79 AD eruption of Mount Vesuvius.

The houses shown in this page were called domus in Latin (hence domestic and domicile).

Façade of House of the Ceii with an electoral advertisement

The ground floor of the larger houses, like that of the modern palaces of Naples, was generally occupied by shops. (..) Where there were no shops, the external walls of the ground floor were always blank, stuccoed, and painted, often with the brightest colours.

John Murray – Handbook for Travellers in Southern Italy – 1853

Apart from the entrance door there were no other openings on the street. It was a matter of privacy and security; rooms received light from one or two open courtyards inside the building.

House of Paquius Proculus: (left) view from the entrance with the “tablinum” in the foreground and the “peristylum” at the end; (right) detail of the mosaic at the entrance; see a fresco from this house at the Archaeological Museum of Naples

The domestic architecture, in short, is entirely that of a people accustomed to pass the greater portion of their day in the open air. Murray

The domus were designed according to a very similar pattern; their overall shape was rectangular with two open areas:

a) the tablinum (close to the entrance) where rainwater was collected in a basin (impluvium) and stored in an underground cistern. This practice lasted until the construction of an aqueduct at the time of Emperor Augustus. The basins then became part of the decoration of the tablinum, the public part of the house where the landlord received his friends.

b) the peristylum, the private part of the house, consisting of a large courtyard around which cubicula (small bedrooms), the kitchen and other facilities were located. Curtains separated the tablinum from the peristylum.

Mosaics depicting a dog or Cave canem inscriptions (beware of the dog) were a warning sign for burglars.

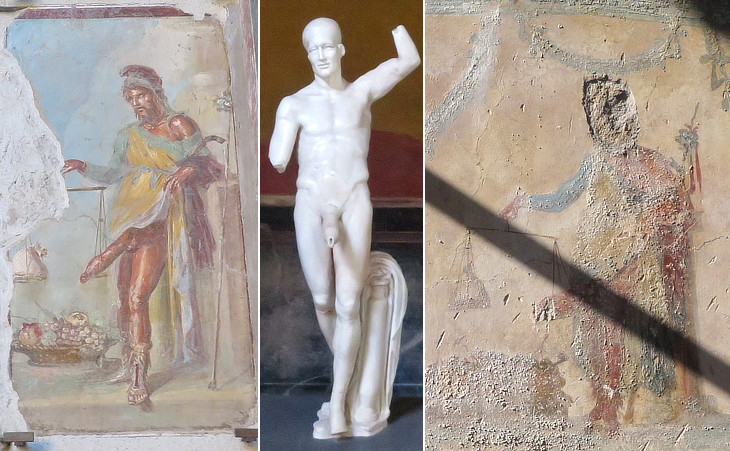

(left/centre) House of the Vettii: painting and statue of Priapus; (right) House of Leda: Priapus

The first side-street on the right leads to the House of the Vettii, excavated in 1894-95. The beautiful paintings found here, as well as the marble decorations of the peristyle (which has been laid out as a garden as in antiquity), have been left in situ. At the entrance is a representation of Priapus (closed). (..) Beside the kitchen is a room (closed) containing paintings not suited for general inspection and a statuette of Priapus from a fountain (probably once in the peristyle).

Karl Baedeker – Handbooks for Travellers: Southern Italy and Sicily – 1900

Dogs protected houses from burglaries and phalli from the evil eye; the portraits of Priapus, a fertility god, were also a symbol of abundance. Those at Casa dei Vettii were attributed also to the bad taste of the landlords, two former slaves who enriched themselves with the wine trade. In 2019 however another portrait of Priapus was unearthed at another house, not far from that of the Vettii. Similar paintings or statues have been found in other parts of the Roman Empire, e.g. at Antequera in Spain.

House of Triptolemus (named after a fresco depicting Triptolemus destroyed by a 1943 Allied bombing): (left) tablinum and peristylum; (right) fragment of a mosaic

It is almost superfluous to add that the names now borne by many of the houses are derived from the paintings which they contained when they were first exhumed, or from the royal personages in whose honour they were excavated. Murray

In many cases archaeologists found painted or carved inscriptions indicating the landlords and the houses were named after them. In other cases they were named after a detail of a mosaic or a fresco or a statue (which may no longer be there because it was moved to a museum or destroyed by WWII bombing). Finally other houses were named after an important personage who visited them (e.g. House of the Prince of Naples). Some of them have two or three names, but all are identified by a code developed by Giuseppe Fiorelli which indicates the neighbourhood (Regio), the block (Insula) and a sequential number. House of Triptolemus (or House of the Cissonii or House of L. Calpurnius Diogenes) is VII.7.7.

(left) Peristylum of the House of the Lovers, thus named after an inscription praising love; (right) painted ceiling of one of the ground floor rooms depicting a trellis for vines or perhaps an aviary (see a Renaissance example at Palazzo Farnese di Caprarola)

The second floor appears to have been occupied as store rooms and as the apartments for servants. (..) We may remark, however, as a curious fact, that no houses have yet been discovered which we can regard as the dwellings of the poor. Murray

Pompeii was covered by a layer of 6m/19ft of ashes. Its first excavators were not interested in ancient walls void of decorations so they very often demolished the small rooms placed on the upper floor around the peristylum. In the XXth century excavations were carried out more carefully. The House of the Lovers was unearthed in 1933 and its upper floor was almost entirely preserved.

Peristylum of the House of Menander (named after a painting portraying the Greek dramatist)

On entering the private division there was a spacious court, called the peristyle, entirely open to the air in the middle, but surrounded by a covered colonnade supported by columns, which answered the double purpose of a passage between the different apartments, and of a sheltered promenade in wet weather. Murray

This very large house belonged to the Poppei family, relatives of Poppea Sabina, second wife of Emperor Nero, who is thought to have owned a large villa at Oplontis, near Pompeii.

(left) House of M. Epidius Rufus; (right) House of Casca Longus: details

The House of Epidius Rufus with a long raised pathway in front, approached by steps from the street, the outer wall painted with numerous inscriptions in red. A narrow prothyrum opens into an oblong atrium, surrounded by a portico of 16 Doric columns, having a fountain in the centre: into this atrium open several small chambers with elegantly painted walls, and on either side wings or wide open recesses enclosed by Ionic columns. (..) At the farther end of the atrium a wide triclinium opens upon an extensive garden: adjoining is a room with paintings of Apollo and the Muses. Murray (1883 edition)

The house was excavated in 1866. Definitely M. Epidius Rufus wanted to impress his guests when he placed sixteen high columns in his tablinum. In September 1943 it was hit by a bomb which demolished all the columns. By saving every little snippet, the columns were reconstructed, but it was only possible to restore a fraction of the entrance from the street. The display of wealth in so many houses of Pompeii, was not unique to this town, which was not particularly important in any sense. You may wish to see a section on Roman towns in today’s Tunisia showing how even small provincial locations, e.g. Thugga, had baths, theatres and houses decorated with extraordinary mosaics.

House of L. Caecilius Iucundus: (left) tablinum; (right) walls painted in yellow, a colour which was less expensive than the red which characterizes many other houses

Had this house been excavated in the XVIIIth century most likely the 150 wax tablets containing accounting records of the landlord would have been lost, but in 1875 archaeologists were already interested in finding out all aspects of daily life at Pompeii and not only objects having an artistic content. The landlord acted as middleman at auctions. He bought or sold on behalf of his customers and he received a commission for his services. Archaeologists found in the house a curious relief depicting the effects of the 62 earthquake and a fresco which was moved to Gabinetto Segreto, because of its subject.

House of the Golden Cupids (see its lararium and altar to Isis, its small and large paintings and its mosaics): garden of the peristylum (see a 1909 painting by Alberto Pisa showing the garden of the House of the Vettii)

The centre of the floor was usually a garden of shrubs and flowers, decorated with statues and fountains. Murray

In the early days the ground of the peristylum was used as a kitchen garden. In a second phase these areas became small gardens adding to the beauty of the building, but some of them had trees providing figs, lemons, apples and cherries to the family.

House of Giulia Felix, one of the first to be excavated: summer triclinium (dining room) with marble couches and small fountains at the back; the room faced a large garden; a part of the property was leased

Furniture, too, you see, of every kind-lamps, tables, couches; vessels for eating, drinking, and cooking; workmen’s tools, surgical instruments, tickets for the theatre, pieces of money, personal ornaments, bunches of keys found clenched in the grasp of skeletons, helmets of guards and warriors; little household bells, yet musical with their old domestic tones.

Charles Dickens – Pictures from Italy – 1846

One of the rooms entered from the peristyle was the dining room, or triclinium so called from the broad seats which projected from the wall and surrounded the table on three sides and enabled the luxurious Romans to recline on couches at their meals. The wealth and magnificence of the owner was generally lavished on the decorations and furniture of this apartment, although it was never very spacious. Murray

House of the Faun: northern peristylum (see its famous works of art, chiefly floor mosaics and a fine 1909 painting by A. Pisa showing the house)

No one could overlook the solemn dignity of aspect which makes the Casa del Fauno conspicuous amidst the mass of habitations in Pompeii. Here beauty reveals itself in column and capital, cornice and panelling, favourably contrasting with the gaudy frippery of a fantastic mock architecture with its pictorial accompaniments. Baedeker

Not all the landlords were able to rebuild/restore their homes after the 62 earthquake. The landlord of the House of the Faun bought that of his neighbour and turned it into a very large peristylum having the size of a palaestra (a place for wrestling/exercising), rather than that of a private garden.

House of Marcus Lucretius

In the rear of the richest houses was an open space or flower garden, called the xystus, which was usually planted with shrubs and flowers, decorated with fountains and statues, and sometimes furnished with a summer-house. Murray

We now regain the Strada Stabiana, which we ascend. To the right the House of Marcus Lucretius, once richly fitted up, though with questionable taste (closed). Behind the atrium is a small garden, laid out in terraces, with a fountain and a number of marble figures. Baedeker

The small rear garden of this house was arranged so that it could be seen from the street. It shows an early use of mosaics for the decoration of small fountains (see another example at Pompeii and a more complete one at Herculaneum).

Long southern portico of Villa of the Mysteries

Dr. Maiuri is indeed to be congratulated on the appearance of the official publication (Amedeo Maiuri – La Villa dei Misteri. Roma – 1931) of the famous Villa Item, or Villa of the Mysteries. (..) The majority of archaeologists will naturally turn most eagerly to those pages of the text in which the author discusses the interpretation of the Great Fresco, the famous paintings from which the Villa has derived its name.

The Journal of Roman Studies – Volume 24 – 1934

In 1909 the owners of Villa Item, an estate outside Porta Ercolano, discovered the remains of a Roman suburban villa. In 1929 professional archaeological excavations were conducted by Prof. Amedeo Maiuri and a very interesting large fresco was discovered together with some interesting small decorative paintings on a black background. The residential part of the complex was sheltered from the sun by a long portico, similar to that which can be seen at Villa di Poppea.

The image used as background for this page shows a stucco laurel wreath placed above the entrance of a house in Via dell’Abbondanza.