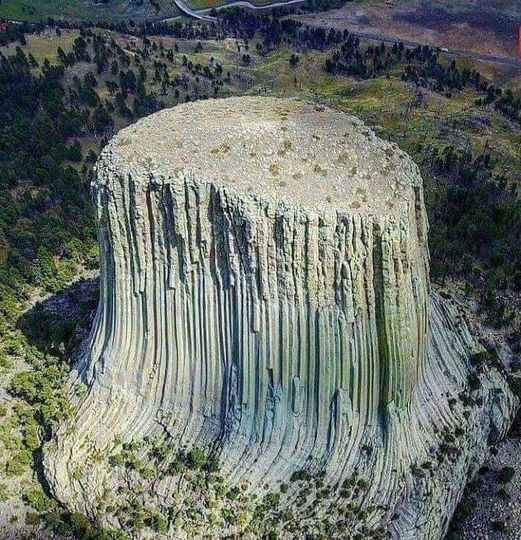

Devils Tower National Monument

“A dark mist lay over the Black Hills, and the land was like iron,” N. Scott Momaday wrote. “At the top of the ridge I caught sight of Devil’s Tower upthrust against the gray sky as if in the birth of time the core of the earth had broken through its crust and the motion of the world was begun. There are things in nature that engender an awful quiet in the heart of man; Devil’s Tower is one of them.” Several Indian nations of the Great Plains share similar legends on the origin of this prominent butte. The Kiowa people say:

“Eight children were there at play, seven sisters and their brother. Suddenly the boy was struck dumb; he trembled and began to run upon his hands and feet. His fingers became claws, and his body was covered with fur. Directly there was a bear where the boy had been. The sisters were terrified; they ran, and the bear after them. The came to the stump of a giant tree, and the tree spoke to them. It bade them climb upon it, and as they did so it began to rise into the air. The bear came to kill them, but they were just beyond its reach. It reared against the tree and scored the bark all around with its claws. The seven sisters were borne into the sky, and they became the stars of the Big Dipper.”

“Bear Lodge” is one Native American name for the Tower. The name Devils Tower was affixed in 1875 by Col. Richard I. Dodge. Gen George Armstrong Custer had confirmed gold reports in today’s South Dakota portion of the Black Hills. Dodge’s Expedition was sent to survey the area. In the late 19th century, science had an explanation for every natural occurrence–or would shortly. Devils Tower was determined to be the core of an ancient volcano.

On July 4, 1893, with fanfare and more than 1,000 spectators, William Rogers and Willard Ripley made the first ascent, using a wooden ladder they had built that spring for the first 350 feet. The fact that they already had a flagpole waiting for the raising Old Glory atop the Tower suggest the “first ascent” might have been one day before. The climber’s wives ran the refreshment stand and sold pieces of the flag as souvenirs. Such was the life in the Old West. The Tower became a Fourth of July meeting place for families from the area ranches, who might see each other but once a year. At the annual picnic in 1895, Mr. Rogers used her husband’s ladder to become the first woman to reach the summit.

Records of Tower climbs have been kept since 1937. Approximately 5,000 climbers come here every year from all over the world to climb, on the massive columns. More than 220 routes have now been used in climbing the Tower.

But there is more to this area than the Tower. Life thrives around its base. Here in Wyoming’s northeast corner, the Black Hills pine forests merge with rolling plains grasslands. At Devils Tower you can see every step in the process of establishing a forest–from bare rock to pines. And because mountains and plains converge here, you may find a great variety of birds. More than 150 species have been counted–including hawks, bald and golden eagles, prairie falcon, turkey vulture, and American kestrel. No one will miss the brightness of the male mountain bluebird, the industriousness of the nuthatches, or the feistiness of the black-billed magpie. Predominant mammals are the white-tailed deer and black-tailed prairie dog. You can spend hours watching busy, playful prairie dogs in their “town” on the grasslands below the tower.

Wildlife has been protected here since 1906, when President Theodore Roosevelt proclaimed Devils Tower the first national monument under the new Antiquities Act. His action made Wyoming the home of the firs national park–Yellowstone in 1872–and our first national monument. During the Great Depression, the Civilian Conservation Corps built road improvements, camping and picnicking facilities, and a museum. The roughhewn log museum still serves as a visitor center, book sales outlet, and the registration office for rock climbers.