Chasing Cervantes in Madrid

Four hundred years ago, on April 22, 1616, Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, died in Madrid. (William Shakespeare died the next day.) Cervantes died in the house on Calle de León that he’d been renting from Francisco Martínez, chaplain of the Convent of San Ildefonso.

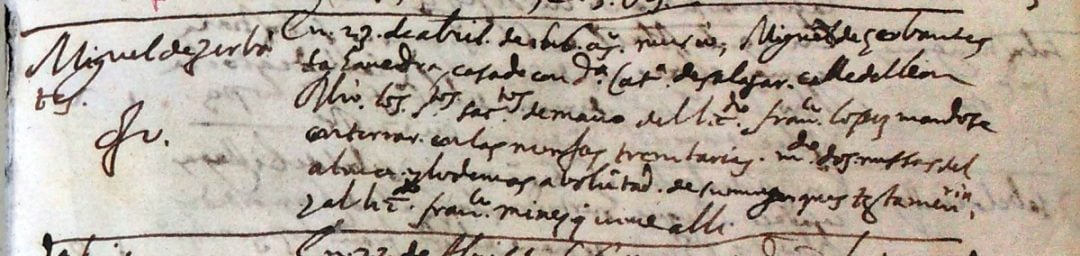

His last will and testament, lost to history, requested that he be buried in the church of the Convent of San Ildefonso of the Trinitarias Descalzas. Cervantes made this decision most likely because nuns at the convent had raised money for ransom to free him from imprisonment in Algiers. He’d been captured by pirates and spent spent five years as a slave, attempting and failing at least four times escape. According to the log of the parochial church of San Sebastián, he was buried in the convent the following day:

En 23 de abril de 1616 años murió Miguel de Çerbantes Sahauedra, casado con Doña Catalina de Salazar, calle de León. Recibió los Santos Sacramentos de mano del licenciado Francisco López. Mandóse enterrar en las Monjas Trenitarias. Mandó dos missas del alma, y los demás a voluntad de su muger, que s testementaria y el licenciado Francisco Martínez, que viue allí.

On April 23 of the year 1616, died Miguel de Çerbantes Sahauedra, married to Doña Catalina de Salazar, on Calle de León. He received the Sacred Sacraments from Francisco López. He is to be buried in the Sisters of the Trinity. Two masses and the rest will be given at the request of his wife, who is the executer of the estate, and Francisco Martínez, who lives there.

At some point, however, when the convent was rebuilt in the 18th and 19th century, his remains, along with others buried in the church, were moved and their location was not recorded. Several searches for Cervantes remains ensued, in 1809, and again in 1870, the latter effort at least resulting in a book published about the fruitless search.

In 2014, the 400th anniversary of Cervantes’ death approaching, Madrid’s City Council commissioned a new search, led by Fernando de Prado Pardo-Manuel de Villena and Luis Avial Bell. Ground Penetrating Radar was used to examine the church of the Convent of San Ildefonso, and, after promising results, Doctor Francisco Etxeberría and Almudena García Rubio led an archeological excavation of the crypt.

I’d heard about the recent discovery of Cervantes’ remains, so on a trip to Madrid in August 2015, I determined to do some exploring of is legacy in the city and, if possible, view his remains. This didn’t prove to be as easy as one might expect.

Cervantes and his immortal characters Don Quixote and Sancho Panza are nearly omnipresent in Madrid. A street performer on the popular shopping avenue Calle de Fuencarral appears as the statuesque Quixote. The magnificent monument of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, with their creator looming above, dominates the Plaza de España. Ubiquitous also are Don Quixote knickknacks, stickers, and posters in tourist shops surrounding the Plaza Mayor. Yet celebrations surrounding the 400th anniversary of Cervantes’ death had not yet kicked into gear, and in fact by April 2016 still had not kicked into gear. And the resting place of Cervantes’ remains seemed to be a state secret. It’s often said that “España es para listos” (Spain is for those in the know) and this proved apt in this case.

I inquired about Cervantes’ remains with some of Yolanda’s friends, and none seemed precisely to know their location, but everyone pointed to the Convent of the Monasterio de las Descalzas Reales (the Convent of the Descalzas Reales, literally the Convent of the Barefoot Royals), which covers an entire city block in the center of Madrid, at Plaza de las Descalzas, a few blocks from the Puerta del Sol and its Kilometer Zero. Due to its central location, I’d passed by the convent’s doors several times over the years but never ventured inside the convent of its church. We walked over one afternoon around 2 pm but it was closed. The next day we tried again; a sign posted outside informed us that it was completely sold out for the day. A guard standing outside, when I politely asked him about Cervantes’s remains, would only reply that the convent and church was closed for the day. We visited to the website of the historical patronage sites, located the convent, and bought tickets (an adventure in patience itself) for the earliest date available, which happened to fall on our last full day in Madrid and the penultimate day of our visit.

On another afternoon, in between my visits with some of the guitar makers of Madrid, we visited a special exhibit at the Museum of History of Madrid, which documented the effort undertaken during successful search for the remains, through a series of remarkable photographs and images by Javier Balaguer, Jaime de Linos, and Gonzalo Tapia.

The first phase of the search for Cervantes involved Ground Penetrating Radar in order to examine the subsoil for graves beneath the church. Electromagnetic anomalies indicated the likely presence of tombs. Work then began on the area considered most likely as the burial site, the crypt beneath the church’s nave. This crypt, entered through a trap door in the Sacristy, with a single window to the street, had its entire floor and portions of the walls covered by pallets and shelves; it appeared that at some point the site had been rented to a publisher for book storage—though it’s unknown if this included copies of Cervantes’ masterpiece. Below the mess, the team uncovered a tile floor that was partially submerged in some areas.

Opposite the room’s only window researchers discovered some thirty-six niches, covered in modern plaster; only one still conserved the funerary inscription of a chaplain. The team painstakingly registered the contents of each of these niches: recovery of the funerary epitaph, examination of the interior by sounding line and endoscopic camera, opening and registering of contents, and anthropological analysis of their human remains. Niches that had an inscription and found intact since the original date were left undisturbed. Some niches held the remains of chaplains, well conserved due to natural mummification processes from the low humidity and cool temperature; others held various individuals, mostly children. The researchers found evidence of continuous reuse of many niches, some held mixed remains and some had intermittently housed more than one individual, others contained tools used by bricklayers, etc.

The crypt floor showed evidence that it had been used as a cemetery; some tiles had rectangular sections similar to graves, but it quickly became apparent that not all the burials followed this practice, leading to a more large-scale archeological approach. The subsoil contained corpses in well-preserved coffins buried somewhat haphazardly in two layers beneath the pavement: the first layer consisted mostly of the remains of infants or small children that were naturally mummified and had some funerary offerings still in good condition; the layer beneath also contained a large number of infants, though less-well conserved and with poorer coffins and offerings.

The researchers converted the crypt and sacristy into laboratories for the analysis of the remains, careful not to disturb the convent’s nuns, who are cloistered. Physical Anthropology researchers set out to identify the age, sex, and stature of the exhumed individuals and study their pathologies, requiring cleaning, inventory, identification, registration, analysis, and storage of the bone fragments of each of more than 350 individuals in varying states of conservation. Anthropologists, experts from the Textile Museum experienced in historical clothing, and other scientists underwent the analysis, a task made more challenging by the conditions of working within the crypt itself.

Between the niches and the cemetery below ground, careful analysis determined that at least twenty-six adults were buried, six women and the remainder male, of which, in turn, nine were chaplains, as well as at least three hundred infants or small children. The cemetery had been used for burial from 1730 to the early 19th century, and the niches used later in that century, with reuse even later.

The researchers discovered a third level of burial beneath the other two; the remains in this substrata included ten adults and five children. Analysis showed that, of the adults, four were males, two females, and four could not be determined; significant deterioration due to age including loss of teeth in the jawbones impeded precise identification. The presence of a coin of sixteen maravedis from the reign of Philip IV, however, as well as textile remnants of a cassock, positively dated the remains to the 17th century. The remains also matched the number of people buried in the original San Ildefonso church between 1613 and 1630, eleven adults and six children, subsequently reburied in the convent after it was built, beginning in 1673. Among the remains were the skeletons of Miguel de Cervantes and his wife, Catalina de Salazar.

Inside fragments of a wooden coffin, etched with the initials “MC,” was a skeleton with ribs damaged from bullet wounds and with a crippled left arm. “When I saw that rib—I thought, ‘We’ve found Cervantes at last!’,” said Etxeberría, the Spanish forensic anthropologist. With no known descendants of Cervantes, DNA testing will likely not prove helpful in this case.

One afternoon I visited the excellent Museo de la Imprenta Municipal/Artes del Libro (Municipal Museum of Print and Art of the Book), where visitors can view examples of printing presses used throughout the history of Spanish letters, including a press similar to the one used to print El Ingenioso Hidalgo Don Quixote de la Mancha. The publication of Don Quixote in 1605 coincided, not coincidentally, with the democratization of the book and of reading. Books, once the purview only of the elite, were now affordable to those with at least some disposable income. In Part Two, Don Quixote visits a printer and is filled with wonder; Cervantes himself would have doubtlessly visited the printer as his book was being published.

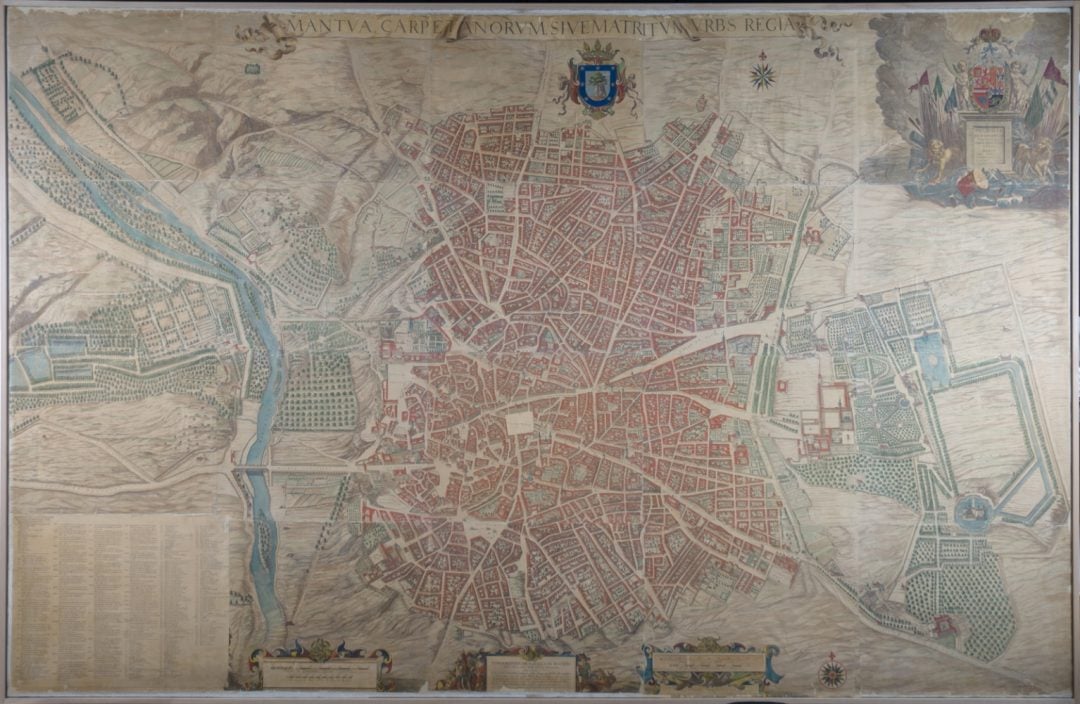

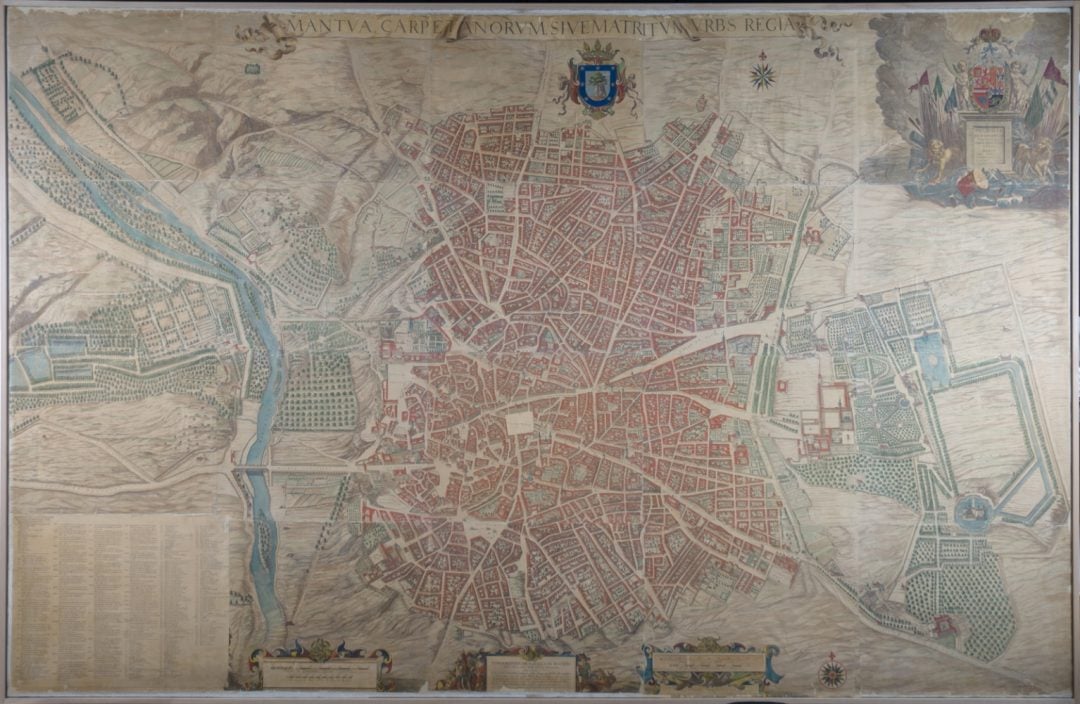

At the Museum of Print, I purchased an excellent facsimile reproduction of a map of Madrid from 1656 by Pedro Texeira. An original hangs in the Museum of History of Madrid. During the period of the publication of Part One and Part Two of Don Quixote and shortly thereafter, the once sleepy town of Madrid was undergoing significant change. The conniving Duke of Lerma had decided to make Valladolid the capital of Philip III’s government, but by 1606 the court had returned to Madrid. In 1616, the construction of the Plaza Mayor had begun, and two years later Phillip III acquired and developed what became the park of El Retiro. It was becoming a new, cosmopolitan Babylon, with a heady mix of nobles, diplomats, clerics, businessmen, artisans, students, courtesans, pretenders, slaves, beggars, and servants. Races, languages, luxury and poverty, vices and virtues mixed in the fetid petri dish of the city’s plazas, streets, markets, parks, and taverns. Texeira’s map, La topografía de la villa de Madrid, is the most detailed and complete map of Madrid from the 17th century and the basis of future maps of the city.

Born in nearby Alcalá de Henares, Cervantes moved to Madrid when young and spent many years in the Spanish capital; several sites in the city are associated with the writer. One worthy site, which I’d visited on another occasion, is the recreation of Juan de la Cuesta’s print shop (calle Atocha, 87), where the first edition of the book was printed. The home today of the Cervantes Society, a replica of the press is at the site and attendants often appear in period dress. (The second part of Don Quixote, published in 1615, was also printed by Juan de la Cuesta, but in another nearby building at Calle de San Eugenio, 7.) Unfortunately, neither the original manuscript nor the printer proof (galley) survived, so we have no knowledge of Cervantes’ process of composing and editing. It is thought Cervantes was paid around 1,500 reales for what would, at the time, have been a substantial print run.

While William Shakespeare imparted more influence over the English language, and coined at least 2,000 words and phrases, more than any writer before or since, with many still used regularly in today’s vernacular, Spain’s Miguel de Cervantes, through his two-volume masterpiece Don Quixote, has had more influence on literature than any other writer in history. After the Bible, Don Quixote is the mostly widely translated and published book in history.

In 2002, editors of the Norwegian Book Clubs, with the Norwegian Nobel Institute, polled 100 of the greatest living authors from 54 countries—among them Milan Kundera, Doris Lessing, Seamus Heaney, Salman Rushdie, Paul Auster, Orhan Pamuk, Wole Soyinka, John Irving, Nadine Gordimer, and Carlos Fuentes—to choose the 100 most central works in world literature, the books that have impacted culture and influenced writers’ own thinking and imagination. Of the 100 titles, presented in alphabetical order, only Don Quixote was cited for special merit, receiving fifty percent more votes than any other book.

Don Quixote’s influence over modern literature cannot be overstated. Cervantes played with perspectives and invented techniques still used by writers from the widest variety of genres. The clash between illusion and reality may be the main theme of Quixote, permeating many facets of the novel, not least the hero, the hidalgo Alonso Quijano who transmogrifies into the knight errant Don Quixote de la Mancha. Cervantes hero may be mad, naïve, an idealist, a fool, a dreamer, a fighter for justice, a superhero or antihero, any and all of these things, and more. Cervantes invented what we refer to today as the mashup, or remix—mixing countless genres and styles, metamorphosing into something new, turning them inside out and against each other.

Last year I reread the book, tackling it simultaneously in Spanish and in English, in print and as an ebook. I’d read a chapter in Spanish, followed by the same chapter in English, from Edith Grossman’s excellent translation. This exercise was both an excellent way to enjoy the book as well as an opportunity to reflect on the art and craft of translation.

The book is narrated from multiple perspectives; Cervantes predominantly deploys omniscient, third person narrators. Cervantes himself appears to be the voice narrating the prologue to Part I, although others have argued it’s an unnamed fictional character, separate from all others in the text (literary scholars debate this ad infinitum, as they do many aspects of the novel). He claims not to be the padre (father) but the padrastro (stepfather, or perhaps editor) of the book; he declares that he consulted the archives of La Mancha and put together the tale from various accounts. But the issue of narrator/author quickly becomes cloudy; by chapter 8 an ambiguous “second author” is introduced, who may be a shadow or may be the translator of the Arabic text, found in Toledo (introduced in chapter 9). This is one of Cervantes’ great metatextual creations: Book Two, not to be confused with Part Two, published in 1615, begins with the discovery of a book written in Aljamía, a form of Spanish or Portuguese written phonetically in Arabic, by a historian, Cide Hamete Benegeli, which is translated as a work for hire by an unnamed morisco, and forms the remaining chapters of Part One, presumably “edited” by Cervantes. (This historian, Cide Hamete Benegeli, is a near anagram of “en fe, Miguel de Cerbantes”—in truth, Miguel de Cervantes.) Other “historical” sources cited by Cervantes/Cide Hamete for this fictional novel include the archives, hearsay and oral tradition, other contemporary accounts, and so on.

In the novel The Ghost Network by Catie Disabato, the author (Disabato) claims to be the “editor” of an academic book written by professor Cyrus K. Archer, complete with footnotes, who narrates the quest to find a missing postmodern pop star named Molly Metropolis. The Ghost Network, which includes multiple perspectives and stories within the story, including histories of fictional sociopolitical movements the Situationists and New Situationists, and alternate words and realities, has the DNA of Don Quixote throughout (whether or not Disabato has actually read, let alone is a fan of, Cervantes, is irrelevant).

Cervantes’ employment of the comedic duo, one tall and gaunt, the other short and rotund, the former an idealist with his head in the clouds, the latter a realist mainly concerned with the realities of life like food and drink, can be seen everywhere from Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson, Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn (Mark Twain was reading Quixote while writing Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn), to Laurel and Hardy, Abbot and Costello, R2D2 and C3PO, and countless others.

The years Cervantes spent as a slave, imprisoned in Algiers, as well as his wide travels in Italy and throughout Spain, led him to incorporate into his narrative voices of those who were formerly the voiceless: Muslims and moriscos (former Muslims who converted or were forced to convert to Christianity), pícaros (rogues), and renegades. He frequently incorporates characters from these disenfranchised individuals as he makes use of a tale within a tale, within another tale, stories like nesting Russian dolls, a metatextual technique exploited by many storytellers after Cervantes. In the second part, the characters of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza become aware that their fame has spread throughout the countryside, due to the popularity of the first book, so much so that characters they encounter want to engage in the full Quixote/Sancho experience.

And their popularity endures. Innumerable movies, animations, TV series, and other adaptions have been made, although unlike Shakespeare’s plays, which are made for a visual medium and are relatively brief, Don Quixote is probably unfilmable in its entirety. The book is, admittedly, overly long with numerous digressions; it would probably take 25-30 hours or more to film the entire narrative. Several film adaptations of Don Quixote were attempted and never completed. Orson Welles tried to film Don Quixote from the 1950s until his death in 1985. Terry Gilliam has tried several times to make a film entitled The Man Who Killed Don Quixote—the 2002 documentary film Lost in La Mancha captures Gilliam’s travails; in 2016 The Hollywood Reporter wrote that Gilliam had received financing for another new attempt. (It’s wonderful to imagine what the Monty Python troop would have done to Don Quixote, like their marvelous send up of the King Arthur legend in Monty Python and the Holy Grail.)

The morning before our flight home via Istanbul, we arrived promptly per our reservation at the Monasterio de las Descalzas Reales for our tour. I’d already come to doubt that this was the site of Cervantes remains, and my suspicions were immediately confirmed—instead of the Monasterio de las Descalzas Reales, Cervantes was buried at the Convento de las Trinitarias Descalzas de San Ildefonso (Convent of the Barefoot Trinitarians). All these descalzas! Nevertheless, the tour was wonderful and well worthwhile. The cloistered royal monastery, founded in 1559 by Doña Juana de Austria (1535-1573), sister of Felipe II and Princess of Portugal, abounds in priceless art, reliquaries, and other religious objects, like a mini El Prado Museum. It was fascinating to tour a site where nuns live secluded and undisturbed in the middle of Madrid, appearing among the public only once per year, and where nobility such as ____ have lived and died. Beautiful, but alas, no Cervantes.

After our tour, we hot-footed it over to the correct site, Convento de las Trinitarias Descalzas de San Ildefonso (Calle Lope de Vega, 18), but of course we were too late, the doors were firmly closed, impervious to knocking at the door, and open only briefly for morning mass. Cervantes will have to wait for our next trip; he’s not going anywhere, anyway.

“Don Quixote’s end came after he had received all the sacraments and had execrated books of chivalry with many effective words. The scribe happened to be present, and he said he had never read in any book of chivalry of a knight errant dying in his bed in so tranquil and Christian a manner as Don Quixote, who, surrounded by the sympathy and tears of those present, gave up the ghost, I mean to say, he died.”