The Oldest Known Globe to Depict the New World Was Engraved on an Ostrich Egg, Maybe by Leonardo da Vinci (1504)

Every time you think you’ve got a handle on Leonardo da Vinci’s genius (which is to say, you think you’ve heard about the most important things he painted, wrote, and invented), yet more evidence comes to light of the many ways he meets the standard for the adjective “genius”.… Recently, Leonardo re-appeared not only as an inventor of futuristic military technology or discoverer of complex human anatomy, but also as the first European to depict the “New World” on a globe–proving he knew about Columbus’ voyages when the globe was made in 1504.

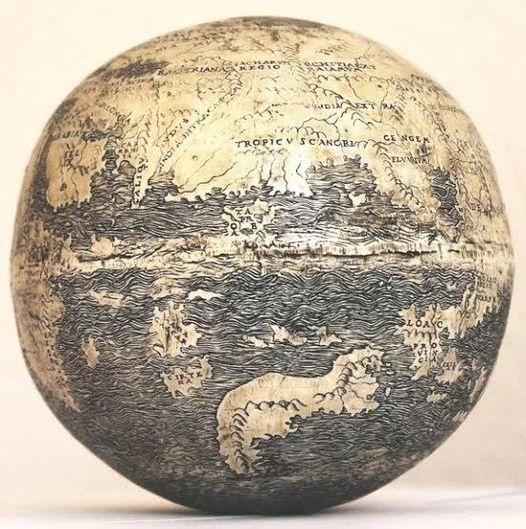

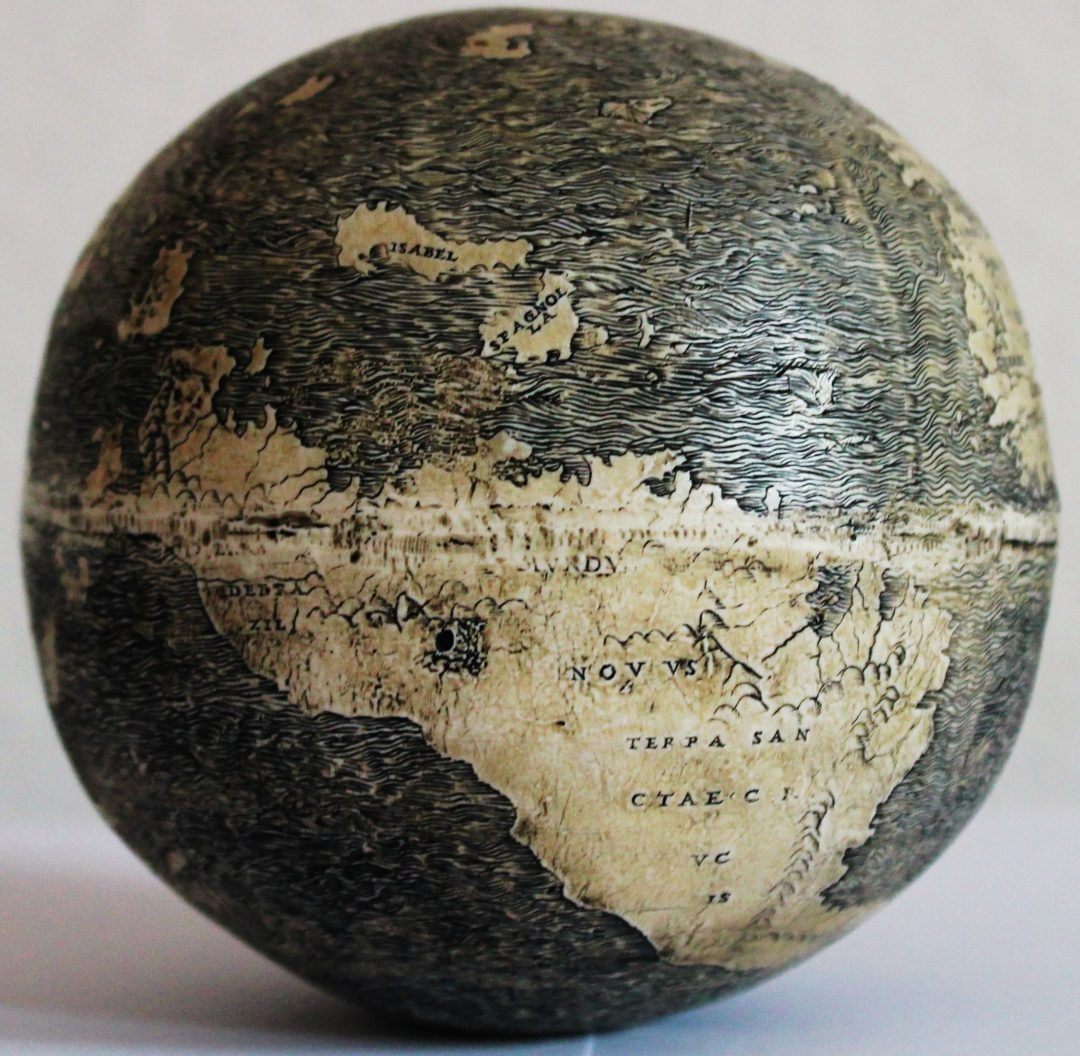

The discovery “marks the first time ever that the names of countries such as Brazil, Germania, Arabia and Judea have appeared on a globe,” notes Cambridge Scholars Publishing, who released a book by the globe’s discoverer and primary researcher, Stefaan Missinne. The artifact attributed to Leonardo is engraved, “with immaculate detail,” writes Meeri Kim at The Washington Post, “on two conjoined halves of ostrich eggs.” And it features a single sentence, in Latin, above Southeast Asia: Hic Sunt Dracones–“Here be dragons.”

We’ll notice other unique features of the engraved egg Missinne calls, simply, “the Da Vinci Globe,” such as the fact that in place of Central and North America are the islands of Columbus’ “discovery,” surrounded by a vast ocean in which Pacific and Atlantic join. Why ostrich eggs? Humans have used them for decorative purposes for millennia. Also, “in that time period,” says Thomas Sander, editor of the Washington Map Society’s journal, Portolan, “the ostrich was quite the animal, and it was a big thing for the noble people to have ostriches in their back gardens.”

Missinne, a real estate developer, collector, and globe expert originally from Belgium, discovered the globe in 2012 at the London Map Fair. It was purchased “from a dealer who said it had been part of an important European collection for decades,” and its buyer and owner remain anonymous. After the globe appeared, Missinne “consulted more than 100 scholars and experts in his year-long analysis,” putting “about five years of research into one year,” says Sander, calling the research “an incredible detective story.”

Missinne’s investigation seems to substantiate his claims that the globe was made by Leonardo or his workshop. The evidence, some of which you can find on the Cambridge Scholars Publishing site, includes a 1503 preparatory map in da Vinci’s papers; the presence of arsenic, which only Leonardo was known to use at the time in copper to keep it from losing its lustre; “The use of chiaroscuro, pentienti, triangular shapes, the mathematics of the scale reflecting Leonardo’s written dimension of planet earth”; and a 1504 letter from Leonardo himself stating, “my world globe I want returned back from my friend Giovanni Benci.”

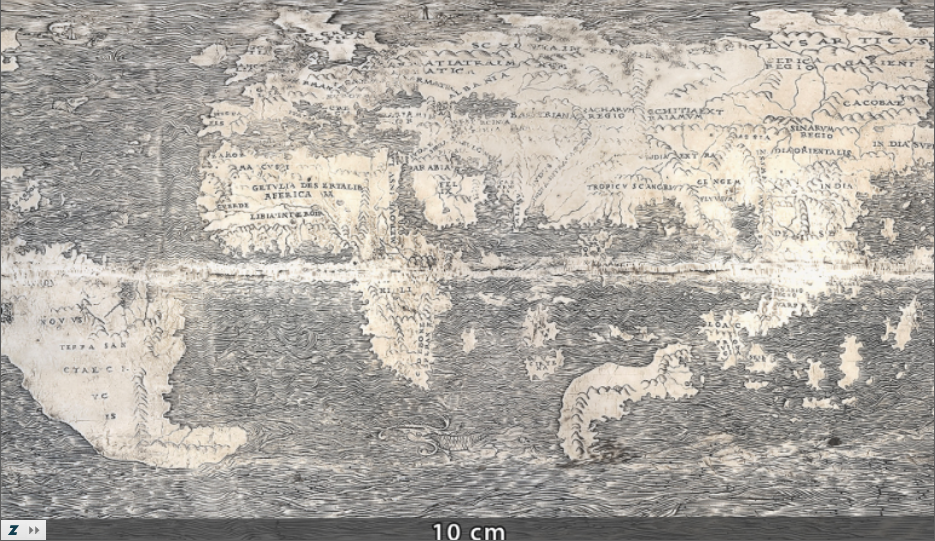

Missinne and Geert Verhoeven, of the Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Archaeological Prospection & Virtual Archeology, have published a paper on the “unfolding” of Leonardo’s globe into the two-dimensional image above (see an interactive version here). “This miniature egg globe is not only the oldest extant engraved globe,” the authors write, “but it is also the oldest post-Columbian globe of the world and the first ever to depict Newfoundland and many other territories.” Previously, the Hunt-Lenox Globe, a small copper globe, was thought to be the oldest known such artifact. Dated to around 1510, this globe, Missinne discovered, is actually a copy made from a cast of the older, original ostrich-egg globe.

Missinne’s findings have their detractors, including John W. Hessler of the Library of Congress, who claims Missinne himself is the anonymous owner of the globe, which raises issues of conflict of interest. “Where this thing comes from needs to be clarified,” says Renaissance cartography expert Chet Van Duzer of the John Carter Brown Library in Providence, R.I., though he adds, “It is an exciting discovery, no question.” Missinne’s claims for the egg’s provenance are more modest than his marketing. He “speculates,” writes Kim, “ the egg could have loose connections to the workshop of Leonardo da Vinci.” Hessler’s view is less equivocal: “The Leonardo connection is pure nonsense.”

A layperson like Missinne, whatever his personal investment, might be inclined to overinterpret evidence or make tenuous connections a trained scholar would avoid. The many scholars he cites in support of his claims for the globe are also vulnerable to these charges, however, though to a lesser degree. What do we make of French Mona Lisa expert Pascal Cotte’s testimonial, “I hereby confirm the evidence of the left-handedness of the engravings on the Ostrich Egg Globe. As Leonardo was the only left-handed artist in his workshop, I hereby endorse the hypothesis of Leonardo da Vinci’s authorship”? As in all such academic debates, “Here be dragons.” Weigh the case in full in Missinne’s 2018 book, The Da Vinci Globe.